The Numbers Tell a Remarkable Story

The food hall market is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.2% from 2025 to 2033, reaching a projected value of USD 62.3 billion by the end of the forecast period. Those aren’t just impressive figures, they represent a fundamental shift in how we approach dining out. With 31% of Americans expecting food hall dining to become widespread in the coming years, it highlights the resilience and potential these spaces hold.

The growth isn’t just happening in major cities anymore. Food halls, once mostly exclusive to cities, now extend to suburbs due to increased demand fueled by remote work during the 2020 pandemic. Among those aware, 71% of city dwellers have tried them, and suburban consumers are not far behind (66%).

What’s fascinating is how different regions are embracing this concept. North America remains the largest market for food halls, representing a significant portion of the broader food service industry, driven by the widespread popularity of food halls in major urban centers and the strong culture of dining out. The United States leads the region, with cities such as New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago serving as epicenters of food hall innovation and expansion.

Psychology of Familiar Spaces

But why do food halls feel so instantly comfortable? The answer lies deep in our psychology. Because familiar things – food, music, activities, surroundings etc – make us feel comfortable. From an evolutionary perspective, it makes sense that familiarity breeds liking.

Think about it: food halls mirror spaces we’ve known our entire lives. According to research, our cravings for comfort food are deeply rooted in psychology. These foods often trigger feelings of nostalgia and emotional comfort, providing a sense of security and familiarity in times of stress or sadness. Food halls extend this concept beyond individual dishes to entire environments.

The architectural psychology at work here is remarkable. From the calming attributes of natural sunlight to the energizing effects of open spaces, architecture influences our behavior in ways we might not always realize. In this article, we will examine important aspects such as how natural light influences mental health, how the arrangement of spaces may facilitate or limit social interaction, and the design elements such as the color of a space or its acoustics and their relationship to human behavior.

The Marketplace DNA

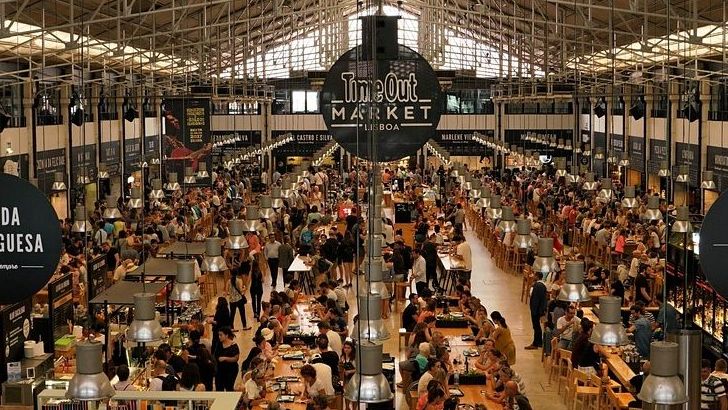

Food halls aren’t actually new; they’re ancient. From Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar to Barcelona’s La Boqueria, a food market is not only for trade but also for the building of community. Pitch dark alleys; halls with barrel vaulting; and covered arcades: they developed to furnish, present, and pass around food. Modern food halls are simply the latest evolution of humanity’s oldest social dining concept.

Markets tell two things about architecture: one, that food is contained, and secondly, that architecture keeps on reorganizing itself in response to how food is grown, sold, and consumed. Anything food-related requires an entire building of its own. This explains why food halls feel so naturally right to us, they’re built into our cultural DNA.

The spaces work because they satisfy multiple psychological needs simultaneously. Food halls do a great job satisfying consumers’ key need-states, says Anne Mills, senior manager of consumer insights for Technomic, which conducted a study on food halls in 2019. “[They’re] a place to grab a quick, convenient meal, a place to socialize and a place to discover new foods or flavors,” she says.

The Comfort Food Connection

Understanding why food halls feel so familiar requires understanding comfort food itself. These results are in line with Troisi and Gabriel’s (2011) finding that comfort foods were “favorite food, a family tradition, a cultural tradition, something eaten for a holiday, something eaten for a significant family event, a part of the participant’s past, or a reminder of home” (p. 750). Food that was offered in a positive, interpersonal context likely activates the contextual positive emotions and feelings of belongingness upon consumption later in life.

Food halls amplify this effect by housing multiple comfort food traditions under one roof. Consistent with and adding to previous literature, we find four recurring themes: (1) familiarity/nostalgia; (2) social surrogacy; (3) warmth/heartiness; and (4) convenience. Consistent with and adding to previous literature, we find four recurring themes: (1) familiarity/nostalgia; (2) social surrogacy; (3) warmth/heartiness; and (4) convenience. Food halls deliver all four simultaneously.

The social surrogacy aspect is particularly powerful. The authors suggested – in line with Zhong and Leonardelli (2008) – that especially in such an extreme setting of societal ostracism, selecting food items that are tied to one’s community may provide a source of comfort and, albeit symbolically, social connection (Wansink et al., 2012). Food halls create instant communities where strangers become temporary neighbors.

Design Psychology in Action

The most successful food halls understand psychological design principles intuitively. Warm shades, which include red, orange, and yellow, inspire feelings of energy, warmth, and excitement. Such colors usually find application in areas such as dining rooms or recreation spaces where high volumes of interaction are prompted to stimulate conversation.

The field of environmental psychology reveals how physical surroundings directly influence mood, behavior, and social interaction. In restaurant design, these principles help us create spaces that subtly guide guests toward desired experiences – whether that’s animated conversation, intimate connection, or community building.

Lighting plays a crucial role too. Lighting is perhaps the most powerful tool for influencing social behavior in restaurants. Warmer, dimmer lighting encourages relaxation and intimacy, leading to longer stays and more personal conversations. Food halls typically use varied lighting to create different zones and moods within the same space.

The Modern Manifestation

Today’s food halls are more sophisticated than their predecessors. These next-generation food halls are developments that have essentially mixed and matched elements from things like farmers markets and public markets and combined them with good old-fashioned food courts,” says a May 2019 report on food halls from Datassential called “Creative Concepts: Next-Generation Food Halls.”

The expansion beyond traditional urban centers is remarkable. “They will continue to expand from large urban areas into smaller towns and into other segments,” Mills says. “For Example, we’re seeing more universities, super-markets and even hotels open food halls.” An Ocala, Fla., Hilton Garden Inn has plans for a food hall on its ground floor and Columbia University in New York City has announced a campus food hall opening this summer, Mills says. “Kroger recently opened a new store in Cincinnati that features a food hall, and Whole Foods plans to open a food hall in a location in Tysons Corner, Va., which will be the chain’s new East Coast flagship.”

The Demographic Drivers

Who’s driving this growth? The data reveals interesting patterns. While food halls appear to be popular among workers across all working situations, those working in hybrid environments (77%) are most likely to have eaten at a food hall, seven points higher than their fully in-person working counterparts and seven points more likely than those working fully remotely (among those aware of food halls).

Modern consumers, especially millennials and Gen Z, are increasingly seeking out venues that offer more than just food; they desire a blend of ambiance, variety, and community engagement. Food halls, with their curated mix of local and international food vendors, artisanal products, and vibrant atmospheres, cater precisely to this demand.

The health consciousness factor is significant too. Additional CivicScience data show food hall patrons are more likely than others to value quality and healthy options. Food hall diners (62%) and intenders (55%) are at least 26 points more likely to be interested in fast-food and quick-service restaurant menu items featuring local ingredients compared to those uninterested in trying food halls (29%).

The Design Philosophy

Creating successful food halls requires understanding human behavior at a fundamental level. First, we like to get an understanding of the neighborhood and its demographic patterns to see the activity of the area at certain hours on weekdays and weekends. After collecting the data, we make it a point to ensure that each tenant receives equal visibility to customers. To achieve this, we provide ample space with a variety of clustered seating options and a strategically planned layout for foot traffic and visibility.

The space planning follows specific psychological principles. As a rule of thumb, it is important for half of the overall food hall to be dedicated to the front-of-house and the other half to be dedicated to the tenants. We usually have one single circulation and a minimum of 10 to 14 diversified cuisines to plug into a space. From there, depending on the area, we add new and fun food and beverage tenants to create the compression of the spaces, making for a diverse and lively food hall. For the seating area, we’ll typically designate 15 square feet per person minimum.

The Future Evolution

Looking ahead, food halls are adapting to new realities while maintaining their essential appeal. Food halls need to respond to the labor shortage and lack of available employees. To combat this, technology solutions are put in place and it is popular to see an increase in touchscreen ordering, robotic chefs/deliveries, ghost kitchens, and remote commissary kitchens within these halls. It is important to note that those tools are to help the efficiency.

The international expansion is noteworthy. The Asia Pacific region is emerging as a high-growth market for food halls, with strong growth potential in major metropolitan areas. Rapid urbanization, rising disposable incomes, and a burgeoning middle class are driving demand for innovative and diverse dining experiences in countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, and Australia. The region is witnessing the emergence of large-scale food halls in major metropolitan areas, as well as the adaptation of the concept to local tastes and preferences.

The Psychological Comfort

Perhaps most importantly, food halls provide what psychologists call “cognitive fluency.” Cognitive fluency is a measure of how easy it is to think about something. The easier something is to understand, the more likely we are to believe it. Food halls make dining out effortless, they remove the anxiety of choice while still providing variety.

The familiarity extends beyond just food to entire cultural experiences. An article by Triosi and Wright pointed out that people either define comfort food as lacking in nutritional value or a food that has meaning, whether it is traditional, familiar, or cultural. They too found that there is a tie between relationships and belongingness in regards to comfort food. Instead, it is intertwined with other aspects of one’s life through emotions, memory, and culture. “Food can be nostalgic and provide important connections to our family or our nation.” When you move to a new country, everything is unfamiliar; however, through food have a way to preserve your culture and it can help provide a sense of familiarity.