The Hidden Truth Behind Every Bite

What if I told you that the next time you bite into your favorite slice of pizza, your nose is doing most of the work? Research shows that the smell of a food accounts for up to 80 percent of how we perceive flavor, making your nostrils the unsung heroes of every meal. Think about it this way – when you have a stuffy nose from a cold, even the most delicious foods taste like cardboard. That’s not coincidence, it’s science revealing something pretty mind-blowing about how we actually experience food. Most people walk around thinking their taste buds are calling all the shots, but they’re only handling about 20% of the flavor party. Your nose? It’s running the whole show. This isn’t just some fun fact to impress friends at dinner parties – understanding this connection is revolutionizing how food scientists, chefs, and even doctors think about everything from weight loss to treating eating disorders.

Your Brain’s Flavor Mixing Board

Smells are handled by the olfactory bulb, which sends information directly to the limbic system, including the amygdala and the hippocampus, the regions related to emotion and memory. Unlike other senses that have to make a pit stop at the thalamus first, smell gets VIP access straight to your brain’s emotional center. 75% of all emotions generated every day are due to smell, and because of this, we are 100 times more likely to remember something we smell over something we see, hear or touch. This direct neural highway explains why the scent of chocolate chip cookies can instantly transport you back to your grandmother’s kitchen, complete with the warm fuzzy feelings. While visual recall of images sinks to approximately 50% after only three months, humans recall smells with 65% accuracy after an entire year. Your brain treats smells like emotional bookmarks, filing them away with incredible precision. When you smell something familiar, it’s not just triggering a memory – it’s recreating the entire emotional experience that came with it.

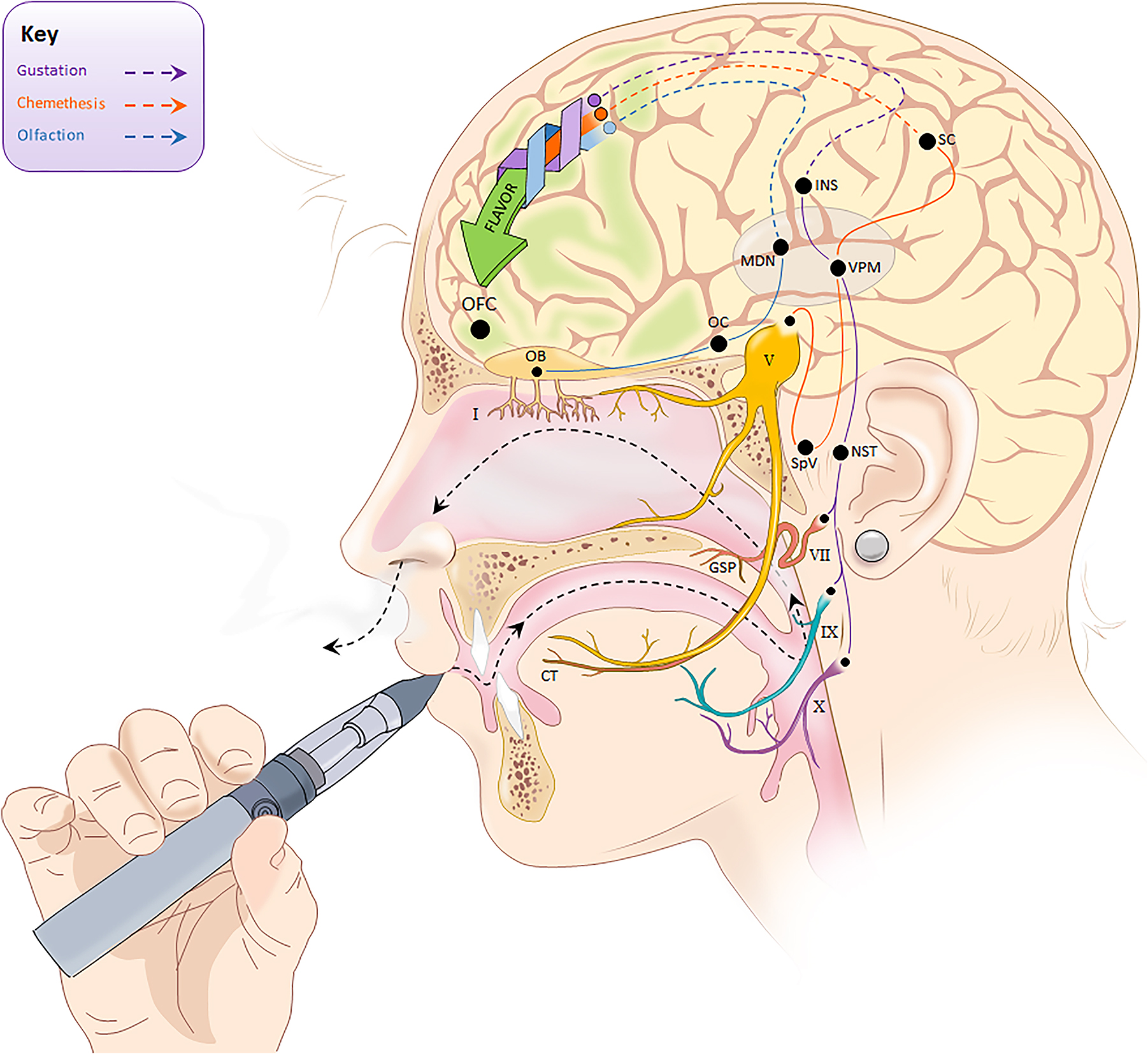

The Magic of Retronasal Olfaction

Here’s where things get really interesting – there are actually two different ways you smell food, and they work completely differently. Smells can arise from a source external to the body and stimulate the olfactory epithelium upon inhalation through the nares (orthonasal olfaction), or alternatively, smells may arise from inside the mouth during consumption, stimulating the epithelium upon exhalation (retronasal olfaction). Think of orthonasal as “sniffing” – when you inhale the aroma of fresh bread from across the room. Retronasal happens when you’re actually eating, and volatile compounds from the food travel up through the back of your throat to your nasal cavity. When you chew, molecules in the food “make their way back retro-nasally to your nasal epithelium,” meaning that essentially, “all of what you consider flavor is smell”. Perception of retronasal olfaction is dependent on expiration, and combining retronasal olfactory information with gustatory information and somatosensation enable us to identify flavors when drinking and feeding. It’s like having two separate smell systems that work together to create your complete flavor experience.

Why Your Taste Buds Are Actually Limited

Without our sense of smell, our sense of taste is limited to only five distinct sensations: sweet, salty, sour, bitter and the newly discovered “umami” or savory sensation. All other flavours that we experience come from smell. Your tongue is basically operating with a five-note piano while your nose has access to a full orchestra. Humans can detect thousands of distinct odours, if not more, compared to our ability to detect only a few types of taste. We have about 400 different receptor types for smell. This means that what you think of as “strawberry flavor” isn’t actually a taste at all – it’s entirely smell. Same goes for vanilla, chocolate, or any of those complex flavors that make food interesting. Many food flavors have no taste at all, like vanilla. Vanilla has no taste, but because of its ‘sweet’ aroma, we think that it does. Vanilla is not sweet, bitter, sour, umami or fatty, yet it is easily recognisable and most people would say that it is sweet. Your taste buds can only tell you if something is sweet, salty, sour, bitter, or umami – everything else is your nose doing the heavy lifting.

The Phantom Aroma Effect

Food scientists have discovered something almost magical called “phantom aromas” – by adding barely detectable amounts of odorants into foods, our brain can perceive flavors without realizing that they are not actually there. It’s like flavor sleight of hand. Research has shown that ham or beef odors make people think that their food is saltier, while vanilla flavor is very strongly associated with sweetness and fools people into believing that there is more sugar in their food than there actually is. An example is adding vanilla to ice cream to enhance the sweetness without adding more sugar. This isn’t just a neat party trick – it’s being used to create healthier foods. Companies can reduce salt and sugar content while maintaining the same flavor perception by manipulating the aroma profile. Research showed that the intensity of perceived salty taste was significantly increased by the sardine aroma when the salt concentration was at a low- or medium-level, and specified odors may induce enhancement of saltiness in low salt solutions, suggesting an approach through which the amount of sodium chloride in food can be reduced without losing any intensity of salty taste.

How Memory Shapes Every Meal

Taste/smell integration is strongly dependent on previous experience with taste/odor pairings, and to date, no study has examined the role of experience on taste–odor integration. Your brain is constantly cross-referencing new flavor experiences against its massive database of smell memories. It’s a seminal passage in literature, so famous it has its own name: the Proustian moment — a sensory experience that triggers a rush of memories often long past, or even seemingly forgotten. For French author Marcel Proust, who penned the legendary lines, it was the soupçon of cake in tea that sent his mind reeling. Seasonal flavors can have strong sensory synchrony amplified by emotions linked to memories of specific events. For example, the sweet-tart taste of lemonade may tie back to sitting lakeside with friends, and a sweet and slightly spiced apple pie flavor can evoke intertwined aroma and taste responses heightened by thoughts of grandma’s kitchen. This is why foods from your childhood taste different than new foods – your brain has years of emotional context attached to those familiar smells. Every time you smell something, your brain is doing a lightning-fast search through your personal flavor archive, pulling up associated memories and emotions that literally change how the food tastes.

The Neuroscience Behind Flavor Processing

Research findings support a view in which retronasal, but not orthonasal, odors share processing circuitry commonly associated with taste, and inactivation of the insular gustatory cortex selectively impairs expression of retronasal preferences. Thus, orally sourced (retronasal) olfactory input is processed by a brain region responsible for taste processing, whereas externally sourced (orthonasal) olfactory input is not. This discovery is huge because it shows that your brain actually processes food smells differently depending on whether you’re just sniffing them or actually eating them. Flavor perception arises from the central integration of peripherally distinct sensory inputs (taste, smell, texture, temperature, sight, and even sound of foods), and the results from psychophysical and neuroimaging studies in humans are converging with electrophysiological findings in animals. Smell is directly linked with emotions – neurologically speaking. The olfactory bulb, a structure at the base of the brain, receives olfactory signals from the nasal olfactory receptors. When you eat, multiple brain regions are working together like a symphony orchestra, with the conductor being your smell system. The fact that retronasal olfaction gets processed in the taste cortex explains why food smells so much more complex and satisfying when you’re actually eating it compared to just smelling it from across the room.

The Modern Food Industry’s Aroma Revolution

The fragrance ingredients market is estimated at USD 17.11 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach USD 21.94 billion by 2029, at a CAGR of 5.1% from 2024 to 2029. The food industry is waking up to the power of smell in a big way. Osmo, a Google spin-off, has developed AI to create aroma molecules for fragrances, combining machine learning, data science, olfactory neuroscience, and chemistry. Givaudan’s Myrissi AI technology predicts the emotional perception of fragrances as part of their 2025 strategy to enhance customer-centered digital solutions. Companies are no longer just thinking about how food tastes – they’re engineering how it smells. The global flavors, indulgent treats and functional foods consumers sought in 2024 have potential to shape 2025’s new product development, with market research firms sharing search data comparing top Google searches for food trends. 2025 is set to be the year multisensory options shape the food and beverage offering, with “little treats” that are unapologetic in the sheer volume of flavor and color combinations that can be tailored to individual tastebuds. This isn’t just about making food smell good – it’s about creating entirely new sensory experiences that didn’t exist before.

Cross-Modal Interactions and Flavor Enhancement

Research measuring both taste and odor intensity showed that sucrose, but not other taste stimuli, significantly increased the perceived intensity of all three tested odors, while enhancement of tastes by odors was inconsistent and generally weaker than enhancement of odors by sucrose. This reveals something fascinating about how our senses interact – sweetness actually makes smells stronger. Certain tasteless substances (especially volatiles) could influence taste perception, and aroma is well-known for its considerable contribution to the perception of taste even in trace amounts, with the “odor-induced changes in taste perception” phenomenon examined in quite a few studies. Think about how different a chocolate chip cookie tastes when it’s fresh from the oven versus when it’s stale – the actual taste compounds haven’t changed much, but the volatile aroma compounds that create that “fresh-baked” smell are what make it taste so much better. It’s not just smell that we associate with taste but colour and sound as well. For instance, red is associated with sweet, green with sour and brown with bitter. Salty and sweet both suppress bitterness, while umami enhances all the other tastes. Your brain is constantly mixing and matching information from all your senses to create what you experience as “flavor.”

Cultural and Individual Differences in Smell Perception

Every culture has its own taste bias which is probably partially genetic and partially influenced by locally available food. Many food companies, including Coca-Cola, change their product formula to conform to these cultural biases – Germans like their Coke spicy, Mexicans prefer it more acidic and Italians want a little bitterness. This isn’t just about different preferences – it’s about fundamentally different ways of processing smell and taste information. Western foods tend to be congruent, with matching aromas, whereas Asian cuisine tends to be complementary. Complimentary foods have different components that go together well, like fish and lemon where the creaminess of the fish protein balances the acidity of the lemon. Some people have many more taste buds than the average person, and therefore have the ability to perceive flavors much stronger and more intensely than others. These “supertasters” experience food in ways that are almost impossible for the rest of us to imagine. What’s fascinating is that these differences aren’t just random – they reflect thousands of years of cultural evolution where different populations developed preferences for the foods available in their environments. Your personal flavor map is shaped by both your genes and your cultural background, creating a unique sensory fingerprint that’s entirely your own.