Falstaff Beer

There was a time when Falstaff stood toe-to-toe with Budweiser in the American beer marketplace, capturing hearts and taste buds across the nation. This discontinued beer that we’re not getting back has changed hands numerous times since it was created by St. Louis-based Western Brewery in 1840. The brand name was sold off to the Griesedieck Beverage Company in 1921 (later renamed the Falstaff Brewing Corporation), and it grew in popularity, reaching top three heights in the United States market by 1960.

Over the next few decades, Falstaff elevated itself from a regional brand into a national one, buying out smaller, struggling breweries in St. Louis and other cities to better produce and distribute its signature lager. The gambit worked – by 1960, Falstaff was the third-biggest American beer company, trailing Anheuser-Busch and Schlitz. But then the inevitable happened – the mighty beer giant stumbled and never recovered. By 1990, only a single plant in Fort Wayne, Indiana, still made Falstaff beer, before S&P discontinued it entirely in 2005.

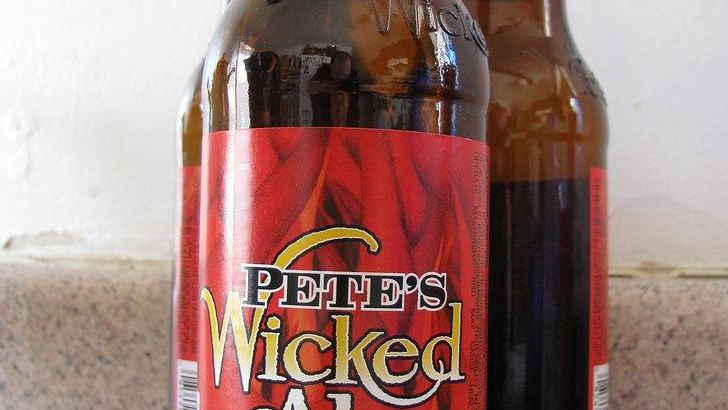

Pete’s Wicked Ale

Some beer stories begin with pure passion, and Pete’s Wicked Ale was exactly that kind of brew. In 1979, according to The Day, Pete Slosberg of Norwich, Connecticut gave up on his home-brewed wine efforts and moved into more time-efficient beer-making. Seven years later, Slosberg first sold Pete’s Wicked Ale to the public – a thick, strong, and flavorful beer and history’s first American Brown Ale. This wasn’t your typical mass-market lager – it dared to be different at a time when American beer meant light and predictable.

It was known for pioneering the craft beer market and went on to become the second-largest craft beer brand in the US. But success brought changes that loyal drinkers couldn’t stomach. After rolling out several more beers, Slosberg sold Pete’s to The Gambrinus Company in 1998. Just two years into its ownership, Gambrinus reformulated Pete’s Wicked Ale to give it a lighter taste. In 2011, Gambrinus sent a letter to distributors announcing that it would no longer make any form of Pete’s Wicked Ale, citing poor sales.

Red White & Blue Beer

Nothing screamed American patriotism quite like cracking open a Red White & Blue beer, especially when it cost less than a dollar for a six-pack. The patriotic name made sense, but Red White & Blue’s biggest selling point was its value. It was a crisp, light lager that was highly drinkable in part because of its low alcohol content – 3.2% – and a six-pack could cost as little as 89 cents in the 1970s.

The beer was so affordable it became legendary for unusual uses. Red White & Blue was so inexpensive that Milwaukee bar The Avalanche used it as the liquid of choice for its “naked beer slide” in the 1980s (per On Milwaukee). But cheap doesn’t always mean sustainable in the long run. In July 2018, the Pabst Milwaukee Brewery and Taproom officially revived the parent company’s old brand, holding a beer garden party and adding the product to the pub’s taps (per Milwaukee Record). Never mass-produced again in bottles or cans, Red White & Blue died off for good when the taproom closed in 2020.

Schlitz Beer

Once upon a time, Schlitz wasn’t just any beer – it was “the beer that made Milwaukee famous,” and that wasn’t just marketing speak. Schlitz first became the largest beer producer in the U.S. in 1902 and enjoyed that status at several points during the first half of the 20th century, exchanging the title with Anheuser-Busch multiple times during the 1950s. This Milwaukee powerhouse pioneered innovations that the entire brewing industry adopted, including the revolutionary brown bottle that protected beer from sunlight damage.

But corporate decisions in the late nineteen seventies sealed Schlitz’s fate in the most spectacular fashion imaginable. In an effort to stem its declining sales and improve its spiraling reputation, the company hired an ad agency, Leo Burnett & Co., to launch four television spots. The commercials featured actors portraying fierce Schlitz loyalists, including a fictional boxer and a lumberjack with a “pet” cougar. In the ads, an off-screen voice asks if they’d like to try a different beer than Schlitz, and the macho men respond with vaguely menacing comments. (“I’m gonna play Picasso and put you on the canvas!”) The ads’ tagline was, “If you don’t have Schlitz, you don’t have gusto.” The campaign backfired so badly it became known as the “Drink Schlitz or I’ll kill you” campaign.

Ballantine Ale

Uploaded by oaktree_b, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=78827751)

In the golden age of American brewing, few names commanded as much respect as Ballantine, a brand that helped define what premium beer could be. P. Ballantine & Sons Brewing Company is a beer brand that was founded in 1845 in Newark, New Jersey. At its peak in the mid-20th century, it was the third-largest brewer in the United States, trailing only Anheuser-Busch and Schlitz. The company’s famous three-ring logo represented “Purity, Body, Flavor” and became as recognizable as any symbol in American brewing.

The brewery had a long sponsorship arrangement with the New York Yankees on television and radio, spanning the 1940s to 1966 (when the partnership was dropped). New York Yankees broadcasts featured commercials with the jingle “Baseball and Ballantine/ Baseball and Ballantine/ What a combination/ All across the nation/ Ballantine, Ballantine beer.” But even Yankees magic couldn’t save the brand from corporate mismanagement. Just three years later in 1972, with losses mounting in the neighborhood of $1 million per month, the investment company sold the brands and distribution network (but not the brewery) to Falstaff for $4 million and a $.50 royalty on each barrel sold. In 1974, the company was forced to declare bankruptcy.

Knickerbocker Beer

New York City once had its own beer royalty, and Knickerbocker was definitely part of that brewing aristocracy. Knickerbocker was the official beer of the New York Giants in the 1950s. That sponsorship likely seemed odd back then, as the beer’s brewer, Jacob Ruppert, actually owned the Yankees at the time. This was beer with serious New York pedigree, brewed by someone who understood the city’s sporting soul.

The son of German immigrants became one of the Empire State’s most prominent brewers, thanks in part to this lager. Ruppert opened his family-owned Uptown brewery in 1913, and in its heyday the operation produced 2 million barrels of beer by the hands of 1,000 workers. It was branded “New York’s Favorite” with its filtered water and sterilized beer that delivered its signature “pure” and satisfying flavor. Until it ceased production in 1965. Knickerbocker Beer had a bit of a reprieve when the recipe landed on the desk of Rheingold Breweries’ owner, but ultimately the Liebmann family (founders of Rheingold Breweries) discontinued the libation in the 1970s. Just like water under the Brooklyn Bridge, Knickerbocker Beer is gone but not forgotten.

Brown Derby Beer

Sometimes grocery stores create legends, and Brown Derby beer was proof that even supermarket brands could capture America’s imagination. Utilizing a process perfected in the 1930s, Safeway brought in northern California beer-maker Humboldt Malt and Brewing Company in 1935 to produce a store brand beer available exclusively at the supermarket’s outlets, primarily located in Western states. That low-cost, pilsner-style light ale was called Brown Derby, and Humboldt was forced by a lawsuit to change its original can’s design featuring a derby hat and umbrella because it looked too similar to the marketing imagery of Los Angeles’s Brown Derby restaurant.

The beer was so popular it created supply problems that most breweries would envy. Regardless of the packaging, Safeway customers bought so much Brown Derby pilsner that Humboldt very quickly found itself struggling to produce enough beer. But corporate changes sealed its fate. Just two years later, the California-based brewery earned the spot as the store brand for Safeway and by the mid-50s, distribution expanded across the company’s network of supermarkets. When Safeway sold off many of its stores to Vons in 1988, the new owners decided to discontinue the grocer’s private-label brew. However, collectors still treasure Brown Derby memorabilia – In fact, a collector shelled out a history-making $93,600 at auction for a vintage can of Brown Derby beer clad in the original infringing artwork.

Meister Brau Beer

Chicago had its own brewing champion long before craft beer became fashionable, and Meister Brau was the Windy City’s pride and joy. Meister Brau has a long history, starting in 1891 in Chicago. It gained local popularity but struggled to gain market share outside the windy city. This was hometown brewing at its finest – a beer that understood Chicago’s working-class soul and served it faithfully for decades.

But regional success doesn’t always translate to national survival in the brutal world of corporate brewing. The brand and company went belly up, leading to its bankruptcy in 1972. Miller Brewing Company acquired the failed brand and discontinued it. However, they reformulated and rebranded it into Meister Brau Lite. The beer exists in spirit today as Miller Lite. In a twisted way, Meister Brau achieved immortality by becoming something completely different – though beer purists might argue that’s not really survival at all.

Billy Beer

Sometimes presidential connections create the strangest chapters in American beer history, and Billy Beer was definitely one of those bizarre moments. You might remember Billy Beer as the short-lived beer brand that Billy Carter introduced and promoted in 1977. Billy was the infamous younger brother of then-President Jimmy Carter. Even with the endorsement, the beer didn’t last long and was discontinued in 1978.

The brand’s downfall came from the most embarrassing possible source – its own celebrity endorser. Consumers found out that Billy Carter reportedly preferred Pabst in private, thereby losing the original appeal that Carter enthusiasts gravitated toward. It’s hard to imagine a more devastating blow to a beer’s credibility than discovering your celebrity spokesperson doesn’t actually drink the product. Billy Beer became a cautionary tale about the dangers of celebrity marketing in the brewing industry, proving that even presidential family connections can’t save a beer that lacks authentic support.

Olympia Beer

The Pacific Northwest had its own brewing royalty long before craft beer made the region famous, and Olympia Beer was the crown jewel of Washington state brewing. The Olympia Brewing Company was founded in 1896 in Tumwater, Washington. The brewery and beer were known for their slogan, “It’s the Water,” as they famously used artesian well water to brew beer. This wasn’t just marketing – the company genuinely believed that their local water source gave their beer a distinctive character that couldn’t be replicated elsewhere.

For over a century, Olympia represented the rugged independence of the American West, served in taverns and backyard barbecues from Seattle to San Francisco. But changing consumer tastes eventually caught up with this regional favorite. Olympia Beer production was temporarily paused in 2021 due to declining demand. It has yet to make a comeback. The silence from Tumwater feels particularly poignant – a beer that once proclaimed the purity of its water source now finds itself unable to compete in a marketplace flooded with craft alternatives and corporate consolidation.

There’s something deeply melancholic about the disappearance of these old-school brews. Each one represented a different piece of American brewing history, from the corporate giants that once ruled the industry to the regional favorites that defined local drinking culture. These weren’t just beverages – they were liquid time capsules that connected drinkers to their communities, their teams, and their traditions. While today’s beer landscape offers more variety than our predecessors could have imagined, we’ve lost something irreplaceable in the process. The simple pleasure of ordering a beer that your grandfather drank, or sharing a brew that sponsored your favorite team for decades, has been replaced by an endless rotation of seasonal releases and limited editions. Maybe that’s progress, or maybe it’s just change. Did you expect that so many legendary names would vanish so completely from the American beer landscape?