Nori: The Gateway to Ocean Flavors

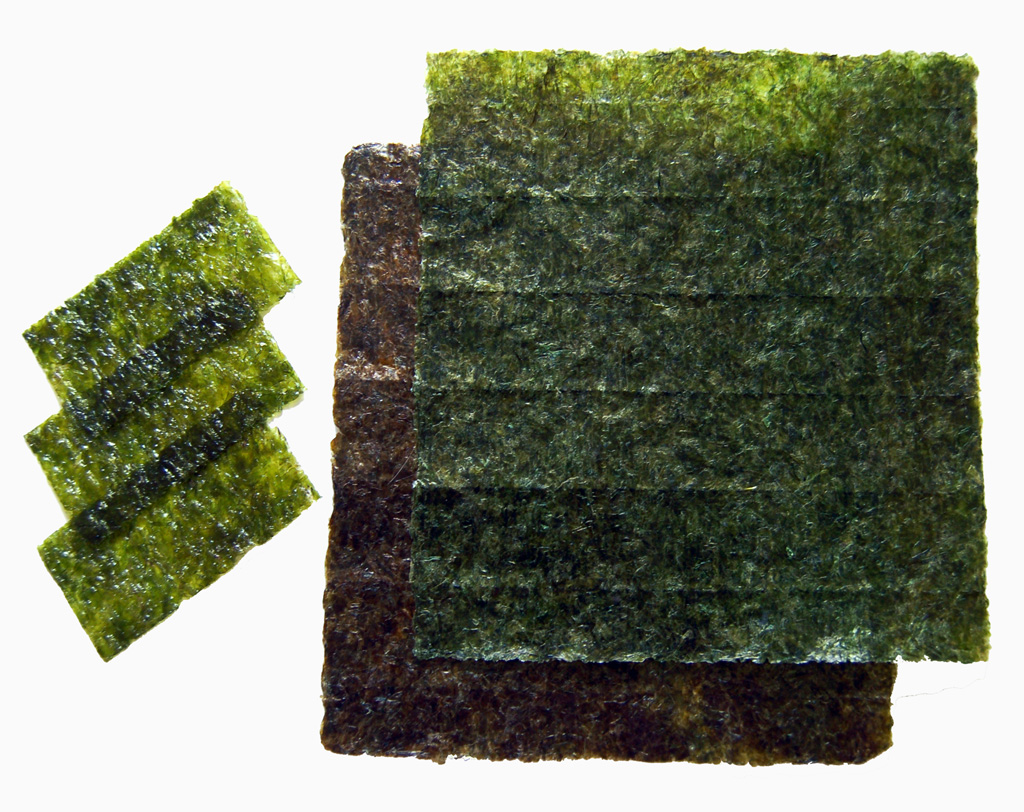

If you’ve ever enjoyed sushi, you’ve already tasted what might be the most familiar sea vegetable on the planet. Nori is probably the best known seaweed in the US and is commonly used as the green wrapping on the outside of sushi rolls. This red algae transforms from its natural deep red state into dark green sheets through careful processing.

This is the mildest-tasting seaweed and is rich in healthy omega-3 fatty acids with less iodine than other varieties. You can buy the sheets toasted or untoasted, and in addition to sushi, nori is commonly used in onigiri (Japanese rice balls) and as a garnish for rice, soups, and stews. Its subtle oceanic taste makes it the perfect entry point for those new to sea vegetables. You can pulse a few sheets of toasted nori in a food processor and add the flakes to dips, soups, and noodle dishes, where nori flakes make a great salt substitute in homemade spice blends.

Wakame: The Silky Superstar of Seaweed Salads

Wakame translates roughly to ‘young girl’ in Japanese, evoking the graceful way it dances in the ocean current and is notable for its thick middle rib and wings on either side. If you’ve enjoyed a warm bowl of miso soup with small green squares in the broth, you’ve eaten wakame seaweed, which turns green and reveals a satiny texture once it’s reconstituted in water.

If you saw it out of the corner of your eye, you might mistake wakame for a leafy green above-ground vegetable because it has a relatively smooth texture and tends to be subtly sweet and silky. After soaking for about ten minutes in water, wakame expands six to eight times its original size, and long strands become really silky and tender. It’s the main ingredient in those addictive seaweed salads you find at Japanese restaurants, but it’s equally delicious in soups and can even be eaten raw.

Kombu: The Umami Powerhouse

Unlike nori, kombu is thicker, smoother, and stronger in flavor because kombu comes from kelp, which is generally hardier than red algae. One of the best ways to taste how sea vegetables can enhance umami is to add a strip of kombu to a pot of beans, where it deepens the beans’ natural flavors while enzymes in kombu break down starches to make beans creamy-soft but not mushy and break down gas-producing sugars.

Kombu is primarily used to make other foods more flavorful, most famously dashi, a broth that’s the backbone of countless Japanese dishes used not just in soups, but also in place of water in doughs and batters like okonomiyaki. Most kombu are harvested from Hokkaidō, Japan though Korea and China also harvest this mildly salty and umami rich vegetable, with Eden Foods inspecting all foods they import from Japan repeatedly to check for radiation.

Dulse: The Bacon of the Sea

Dulse is a type of red seaweed with deep red, purplish fronds and a palm-like shape that grows in the cool waters of the Northern Atlantic and Arctic oceans and is hailed as a great bacon substitute because of its salty, savory flavor. You can find dulse in whole-leaf, flaked, or granule form, and even smoked varieties, where it’s soft and chewy and doesn’t require any soaking or cooking, though when you pan-fry dulse in a little oil, it takes on a distinct bacon-like flavor.

Dulse is a beautiful red seaweed known for its rich, meaty flavor that is native to the North Atlantic/Gulf of Maine and is often sold out of bags at markets in Canada, Ireland and France, where it has been part of local cuisine for generations. During the Irish potato famine of 1845, foraging for dulse was common in Ireland and this seaweed became a substantial dietary staple. There is a definite hint of bacon taste in fresh dulse, though there are other tastes more easily associated with the seaside, and it looks like a type of red lettuce but has more crunch and texture.

Sea Lettuce: The Verdant Ocean Green

Sea Lettuce is a bright green seaweed that grows in tidal areas and even looks a bit like lettuce, is nutritionally dense, full of iron, magnesium and calcium, and moderate in its iodine content compared to other seaweeds with its distinctive flavor making it a great addition to soups and salads, as well as desserts. Ulva lactuca, or sea lettuce, is a type of green algae that grows around coastlines globally and slightly resembles very delicate-looking lettuce leaves, hence its name.

Sea lettuce belongs to the green algae family and is one of the most common types of seaweed found in coastal waters around the world, often used in Asian cuisine with a slightly salty taste and a crunchy texture, often used as a wrap or as a salad ingredient. Research into sea lettuce has demonstrated that it contains a broad range of minerals in significant amounts, though depending on where it grows, sea lettuce can also be a source of heavy metals such as lead.

Arame: The Sweet Newcomer’s Friend

Eisenia bicyclis, commonly known as arame, is a type of brown algae processed, packaged, and sold in a dried state with a dark and brittle appearance that is often added to soups and stews as seasoning. Like hijiki, arame is a brown algae, albeit with a milder taste, where young, tender wild plants are harvested in late summer, finely shredded, and processed into a seaweed that is sweet and delicate, working well in salads, stir-fries, and noodle dishes.

Arame’s considerably milder aroma and taste make it a good choice for anyone just beginning to use sea vegetables, and because of its more delicate texture, arame needs only five minutes of soaking compared to hijiki’s ten minutes. As the water boils, the seaweed reconstitutes and starts adding a lot of flavor to the dish with hints of umami-like flavors and a slight saltiness, and can also be cut into long thin strips for use as a flavor-enhancing ingredient in stir-fries. It has a vaguely sweet taste and a firmer texture than other varieties.

Sea Grapes: The Ocean’s Caviar

Caulerpa lentillifera is better known by the names sea grapes and green caviar and is a type of green algae that does look like small balls of green caviar, with commercial cultivation exclusive to Asia and most of it coming from Japan and the Philippines. Probably the most unique sea vegetable on our list, sea grapes look like a cluster of small green grapes with tiny green bubbles that have a texture and pop similar to fish roe and are salty, sweet, and slightly acidic where the small pearl-like clusters pop in your mouth like real fish caviar.

In Okinawa, Japan, it is known as umi-budō, meaning “sea grapes,” and is served dipped in ponzu, made into sushi, added into salads, or eaten as is. Fresh sea grapes aren’t widely available outside of Asia, but they can be purchased from online specialty stores in their dried form. Sea grapes contain a range of beneficial nutrients based on animal research, though there is a lack of human research on this food and one potential problem is that food poisoning can be an issue, so the seaweed requires careful and appropriate storage.

Irish Moss: The Celtic Thickener

Chondrus crispus is a type of red algae more commonly known as Irish moss with a reddish-purple color that is a rich source of fiber, protein, vitamins, minerals, and polyphenols, and despite the name, grows from the United States to Southern Europe, and as far East as Japan. Irish moss is a type of red algae that grows along the rocky coasts of North America, Europe, and North Africa, also known as carrageen moss or carrageenan moss, commonly used in Ireland and other European countries as a thickening agent in soups, sauces, puddings, and other foods.

Like many other seaweeds, Irish moss tends to be used in soups and stews rather than eaten fresh, and is also used to produce significant amounts of carrageenan, a thickener used within the food industry. Irish moss is rich in several nutrients important for health, including iodine, calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, selenium, and zinc, and also contains carrageenan, a type of fiber that may have several health benefits. This hardy seaweed has been sustaining coastal communities for centuries with both its nutritional value and its practical applications in food preparation.

Hijiki: The Controversial Delicacy

Hijiki is a type of brown algae that is popular in Japanese cuisine with a long, thin, blackish-brown appearance and a slightly sweet, ocean-like flavor, harvested from the wild and then dried and sold in packaged form. Hijiki has long been part of the Japanese diet and is particularly prized for its high calcium and iron content, where Mitoku’s supplier specializes in harvesting and preparing wild hijiki using traditional methods, and its rich flavor and delicate texture make it a wonderful addition to grains, stir-fries, and salads.

Due to concerns about arsenic accumulation in rats fed hijiki, several governmental agencies have advised their citizens to avoid the consumption of hijiki, including the United Kingdom’s Food Standards Agency. Hijiki has come under fire for containing inorganic arsenic, which can be harmful at high levels, making arame a safe substitution to use in recipes if you want to avoid hijiki, with some countries including Canada issuing warnings to limit consumption. Hijiki is thicker, somewhat coarser, and has a strong ocean flavor compared to arame.