When Marketing Collides With Reality

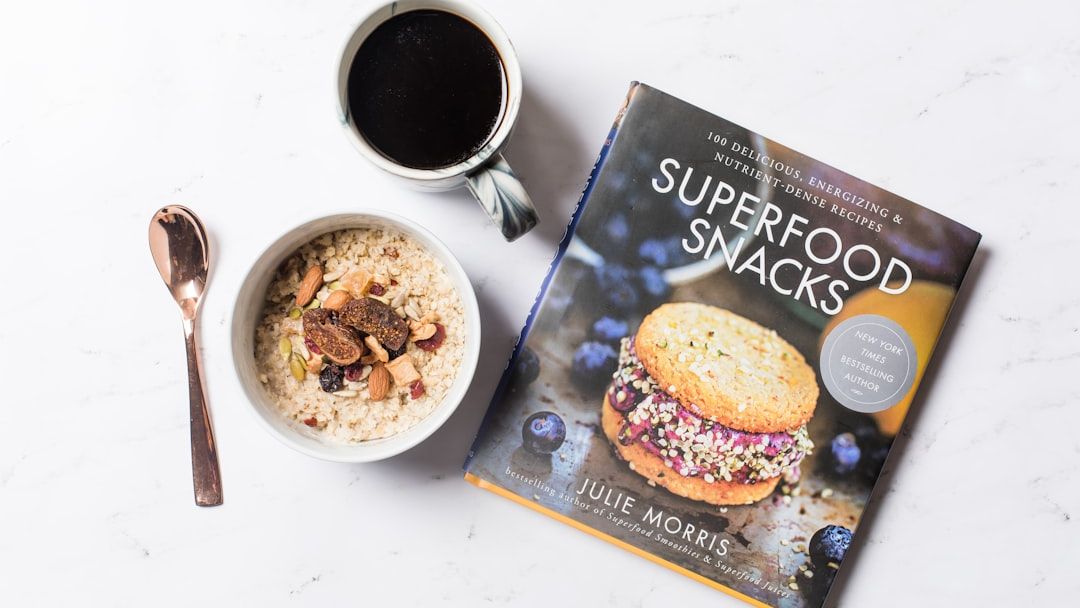

You’ve probably seen them everywhere – from your coworker’s Instagram feed to the shelves of upscale grocery stores. Acai bowls, spirulina smoothies, goji berries by the handful. Superfoods are often nutritious but it’s clear that the term is more useful for driving sales. These products promise everything from reversing aging to preventing cancer, and frankly, the hype is exhausting.

Here’s the kicker: while consumers chase exotic berries and ancient grains, they’re also burning through wellness dollars faster than they realize. These dollars can boost your wellness budget by 40% or more but often expire quickly if not used. Between pricey superfoods and fleeting wellness credits, Americans are caught in a strange financial trap of their own making.

The Rise of the Wellness Credit Economy

The 2025 Wellness Credit is a premium reduction of up to $750 annually according to corporate wellness programs like Chevron’s. Rhode Island employees, for instance, can earn up to $500 in co-share credit incentives ($700 for those enrolled in the Anchor Plan). That sounds generous, right? The problem is that these credits come with strict deadlines and confusing rules.

Credits are granted on a “use it or lose it” basis, explains the University of Calgary’s wellness program guidelines. If your employment status changes or you miss submission deadlines, those funds vanish. Some accounts come with a “use it or lose it” rule, leaving employees scrambling each December to spend money they’ve earned but might lose.

Let’s be honest – wellness credits should simplify healthy living, not create an annual panic attack. Yet here we are, watching thousands of dollars evaporate because we forgot to submit that gym membership receipt by March thirty-first.

The Superfood Industrial Complex

Superfoods is technically a term that was created for marketing, according to Mayo Clinic dietitians. The word has no scientific definition and isn’t recognized by regulatory bodies. Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EFSA do not recognize or regulate the term. It was coined by food marketers and influencers to make certain foods appear superior.

As many as 40% of people may be willing to pay more for foods that provide a health benefit. There has been a three-fold increase in the number of foods and drinks labelled superfoods between 2011 and 2015. That’s not a trend – that’s an industry capitalizing on anxiety about health and mortality.

Take acai berries, which have become the poster child for superfood marketing. Almost all products referred to the large concentration of antioxidants in the acai berry and made various health claims. About a third claimed that acai berries could help with serious diseases like cancer or heart disease. These aren’t minor exaggerations – they’re potentially harmful misrepresentations that prey on vulnerable consumers.

The term is “nutritionally meaningless,” Marion Nestle, professor in the department of nutrition at New York University, writes. No single food will save you, no matter how many syllables are in its name or how far it’s traveled to reach your plate.

Where Your Wellness Money Actually Goes

American consumers spending more than $6,000 per person annually on wellness, according to the Global Wellness Institute. That’s not chump change. The global health and wellness market is predicted to be worth more than six trillion U.S. dollars by 2025. The industry is booming while your wallet gets lighter.

When you factor in those wellness credits from employers – which range from hundreds to thousands of dollars – the pressure to spend becomes intense. Employees feel compelled to use credits on trendy wellness products before they expire, often gravitating toward the most hyped options rather than what’s genuinely beneficial.

Let’s say you have a $50,000 internal budget for wellness. Your insurance provider offers an additional $20,000 in wellness dollars. Now you’re working with $70,000 in program funding. Companies treat this like found money, but for individual employees, it creates confusion about what to prioritize.

Roughly one-third of wellness spending goes toward health products, according to market research. The rest gets distributed across services, fitness memberships, and increasingly, overpriced superfoods marketed as essential to optimal health.

The Science Says Otherwise

Scientific evidence for their beneficial effectiveness and their “superpower” are yet to be provided, according to research published during the COVID-19 pandemic when superfood consumption surged. Health professionals emphasize that the scientific study of nutrition is complex and that sweeping claims about certain foods are often unsupported by comprehensive evidence.

Many superfood claims are based on laboratory studies conducted in test tubes or on isolated compounds, which don’t necessarily translate to benefits when consumed as whole foods in normal quantities. The research is often misrepresented or taken out of context in commercial messaging.

Consider blueberries, which have been labeled a superfood for years. Blueberries were heavily promoted as disease fighters even if the science was weak. The USDA retracted the information and removed the database after determining that antioxidants have many functions. Despite the retraction, blueberry production doubled. The marketing worked even after science pulled its support.

Studies, including those published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), have debunked the exaggerated benefits of antioxidants when consumed in isolation. Eating one miracle food won’t offset poor dietary patterns or unhealthy lifestyle choices. It’s that straightforward, yet the industry keeps selling the fantasy.